OPINION

Special Panigale marks Bologna’s biggest mistake of all time

Ducati has called ‘time’s up’ for the L-twin engine in its sports bikes — and The Bike Shed Times editor and long-time Ducati L-twin lover PETER TERLICK is not happy.

I THINK I’m going to cry. Someone, please, tell me it isn’t true. And more importantly, help me tell Ducati they’re making a monumental mistake.

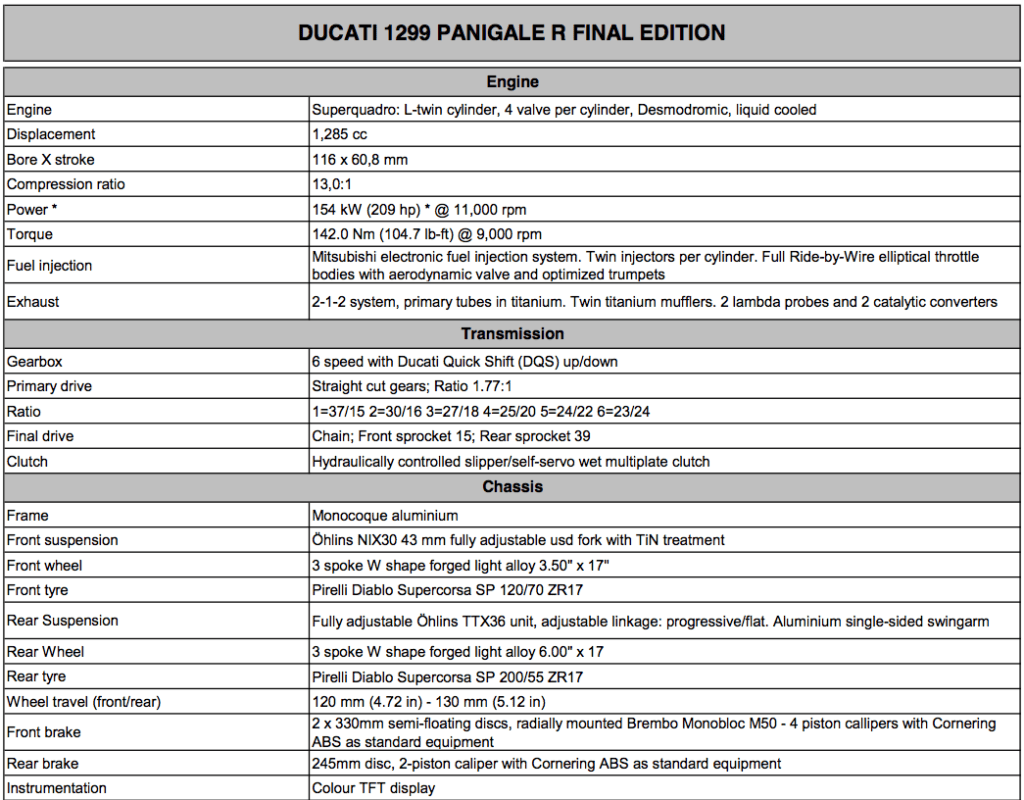

Ducati has released details of a special edition sports bike called the Ducati 1299 Panigale R Final Edition.

Final Edition? Final?

Say what?

And as far as I can make out, this is not just the end of the Panigale. Ducati intends this to be the end of their twin-cylinder sports bikes.

A British website has described the announcement as “a cheery farewell to the V-twin engine”.

I’m going to politely ignore the reference to the Ducati engine as a V-twin (philistines), but ‘cheery’?

Cheery?!

What, like a cheery horror movie?

Like a cheery downpour of rain at an outdoor wedding?

Like a cheery ten-car pile-up on the freeway?

Like a cheery pet-dog-run-over-by-a-Mack truck?

Like a cheery funeral?

Apparently we don’t want twin-cylinder sports bikes any more. Apparently the future is in V4 engines.

Well, Mr Ducati, I have news for you. This is a bad call. Your sports department has beaten up your marketing department, and you’re going to be sorry.

Just as the corporate takeover vultures circle the sky overhead, you’ve made the worst decision in your company’s history. Go ahead with it, and Ducati will go the way of Vincent, Brough Superior and Maico. The world’s greatest motorcycle companies. Gone.

Let me recount a story from the pages of another iconic European motoring company’s history that I’m sure you already know, but with which the folks in Bologna would do well to reacquaint themselves.

Let me recount a story from the pages of another iconic European motoring company’s history that I’m sure you already know, but with which the folks in Bologna would do well to reacquaint themselves.

Way back in 1948, a German bloke named Ferry Porsche took a Volkswagen Beetle (which had been created by him and his father, Ferdinand) and turned it into a sports car.

They called it the Porsche 356. It was beautiful, it was stylish, it was quite fast (for a hot Beetle), and it was cute.

But fifteen years later Ferry’s son, Butzi Porsche, bravely said: “I’m sorry, Vater, but dat is not a sportz car.”

Young Butzi added two more cylinders, beefed it up, made it way fast, made it way sexy, and said to his father: “Now dat is a sportz car.” Butzi had created the Porsche 911.

The 911 took the world by storm. And, as the years went by, the car became much more than the sum of its parts.

It became an institution. It not only carried the company financially, it defined the company’s very existence. Yes, the 911 had a predecessor, just as Ducati’s L-twin engine has parallel-twin and single-cylinder predecessors. But in the eyes of the buying public, the 911 wasn’t just a component of Porsche, it was Porsche.

But the passing years also brought doubters and nay-sayers. By the mid-70s, the hand-wringing reached all the way into the Porsche boardroom and, in 1977, Porsche managing director Ernst Fuhrmann convinced old man Ferry that it was time for change. It was time for Porsche to build a V8.

The old horizontally-opposed flat-six had had its day, they said. The technology was old, they said. The design had run its course, they said. Buyers wanted something new. Gosh, even all the motoring journos were saying its time for something new. (Sound familiar?) And while we’re clearing out the shed, Fuhrmann said, we might as well get the engine out of the boot and move it to the front, where proper cars have their engines.

And hey, let’s give it a radiator, because radiators are modern.

And so the Porsche 928 was born — not just as a new model, but as a replacement for the 911. The motoring world’s collective heart sank. It was like the day they sent Black Beauty to the knackery.

But then, just as the guillotine blade was hurtling to the floor to decapitate the poor, wonderful old 911, Ferry recruited a new CEO. An American, would you believe, by the name of Peter Schutz.

Just four years ago, good ol’ Schutzy wrote these words for a magazine article:

“When I joined Porsche, I hadn’t so much as sat in a 911. But within a week or so of being on the job, I noticed a sort of pervasive sadness among the staff. Asking around, I discovered that the employees had lost all of their motivation as soon as the decision came down to cancel the 911. As the board saw it, the car had become an “outmoded concept.” Sales had been dropping steadily for more than a year, and dealers had begun to complain that the price was too high and quality too low. The 911 was too difficult to control, blah, blah, blah. The decision didn’t sit well with me. While the car could be temperamental at times, at least it had character. That’s what people loved most about it. You had to remain vigilant with your inputs, but for those who could—those with training, with skill, who could catch it in a slide and bring it back into line—the 911 was king. It was the only car worth driving because it was the only car that would push back.”

Mr Schutz could see the problem. In killing the 911, the board of directors was going to kill the company. They thought they were giving the company a new heart, but they were wrong. They were about to remove its heart altogether. Without the 911, Porsche would die. Schutz knew what had to be done. And, in a move that must have gone close to being his last with the German car-maker, he did it.

“You have to understand that, in Germany, once a decision is made, it’s made. As far as the company was concerned, the 911 was history. But I overturned the board’s decision in my third week on the job. I remember the day quite well: I went down to the office of our lead engineer, Professor Helmuth Bott, to discuss plans for our upcoming model. I noticed a chart hanging on his wall that depicted the ongoing development trends of our top three lines: 911, 928, and 944. With the latter options, the graph showed a steady rise in production for years to come. But for the 911, the line stopped in 1981. I grabbed a marker off Professor Bott’s desk and extended the 911 line across the page, onto the wall, and out the door. When I came back, Bott stood there, grinning.”Do we understand each other?” I asked. And with a nod, we did.”

Peter Schutz did not just save the 911.

He saved Porsche.

Please, someone … save Ducati.

Grow up! Big twins & singles are to be phased out through out the world due to emission laws. Ducati are not going to make a Honda clone; they will make an Italian super bike. You will love when you ride it.

If I wanted a V4 or L4 I would have been riding a Honda VFR for the past 20 years.

I never did and I never will.

BMW once announced the boxer twin was ending also. They couldn’t do it in the end because it’s always been synonymous with BMW. I suspect there will be a V-twin running alongside the V4 for sometime to come.

Couldn’t agree more. Long story short, if I ever get a Duke (and I seriously hope I do), it’ll be a twin, or I won’t bother.