OUR recent story on West Australian Ian Boyd’s collection of Vincents struck a chord with many readers. Here’s a tale about one Vincent Black Shadow in Tasmania, and the extraordinary life it led before being retired to a museum.

ALMOST 15 years ago, Tasmanian Andrew Von Stieglitz set out to find his father’s long-lost 1948 Vincent Rapide. But the journey took an unexpected turn when he found half of the Rapide inserted in a substantially more valuable Vincent Black Shadow. DAN TALBOT reports.

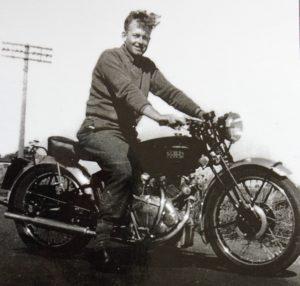

ANDREW Von Stieglitz has a fondness for GT Falcons and Vincent Motorcycles. As a young man, Andrew was drawn to the world of high-performance motorcycles and fast cars and, like many of us, probably looks back in wonder that he made it to middle-age.

Andrew was introduced to Vincent motorcycles by his father, David, who bought a new Series B Rapide in Launceston, Tasmania, in 1948. Years later when it came time for Andrew to immerse himself into the world of classic motorcycles there simply was no contest; it had to be a Vincent. And not just any Vincent. Andrew set about locating his father’s old Rapide — and, in 2003, he found it.

Well, some of it.

Two bikes in one — and a new search begins

It turns out, the Rapide engine had been installed in a Black Shadow by Tasmanian racer Graham White. Graham’s widow was selling the bike — and she was pleased to see it go to the son of the engine’s original owner.

Having secured the bike, Andrew’s focus shifted from finding his father’s bike to tracking down the lost motor from the Shadow. Instead of this being the end of his journey of discovery, it was the beginning.

Andrew’s research revealed the Black Shadow had been purchased new in 1951 in Melbourne by Tasmanian John Parkinson who saw the bike sitting in a Melbourne dealership while on his way to Bathurst.

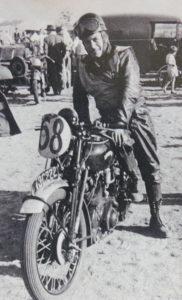

He bought the bike and took it back to Tasmania where he rode and raced it for about 18 months before selling it to a Graham White.

White was a prolific racer and enjoyed success on the Shadow in solo and sidecar guise before robbing its engine for service in a small hillclimb car.

The Phil Irving connection

Hillclimbing in Australia was quite a popular sport during the 1950s with the 1500 cc class being well populated with purpose-built Coopers and a swag of specialist cars using motorcycle engines to stay within the 1500 cc limit.

JAP engines were popular but the Vincent Black Shadow was the pick of the bunch.

Andrew’s search for the Black Shadow engine revealed it eventually wound up in a supercharged hillclimber put together by Australian Grand Prix champion Doug Whiteford and, supposedly, the very man who created the V-twin Vincent motor, Australian engineer Phil Irving.

It is not known for certain whether Irving had any involvement in the development of the Whitford-Irving car but, up until this time, hillclimb specials with Vincent engines were referred to as Vincents but Whiteford’s was referred to as ‘an Irving’.

In his 1997 autobiography, Phil Irving frequently refers to the relationship he enjoyed with Doug Whiteford so it’s not stretching the bounds of credibility too much to conclude Irving likely had some physical input with the Whitford-Irving special.

The Whiteford-Irving car was by all accounts very successful. In 1959, just two months after he purchased it, Lex Sternberg had a stunning win at a Hillclimb in Penguin, described by a journalist at the time thusly: “(Lex) wiped the floor in the derby class with his stove hot (and most handsome) Whiteford-Irving with a blown Vincent engine.”

The trail goes cold; then hot!

The car was campaigned in Tasmania for several years before it was parted-out. The engine went off to New South Wales, and that’s where Andrew’s trail went cold. After a couple of years hunting for the Black Shadow engine he gave up on the search and tidied the Rapide for display in the Launceston Motor Museum. The motorcycle was displayed with a message similar to ‘desperately seeking an engine.’

In 2012, Andrew received a phone call from a person inquiring about purchasing the motorcycle. Andrew declined any offers to sell, but the conversation subsequently led to a discovery — the original Black Shadow engine cases still existed! Some years earlier they had been taken for crack-testing to a company in New South Wales but were never collected.

The cases were dumped in a skip-bin at the rear of the premises destined for scrap but, akin to someone finding a genuine Nolan painting at a garage sale, the cases were retrieved by a young employee who recognised they might have had some value.

And indeed they did.

We trust that young man was suitably rewarded because along the journey to be reunited with the bike, the cases yielded substantial profits for some people. The cases presented an opportunity to return another Vincent Black Shadow to the road and, in so doing, would increase the value to Andrew’s Vincent by about a third.

Having obtained the cases one could be excused for thinking that’s a long way short of an engine. To return to the GTHO Falcon analogy, it has been said that only 500 GTHO Falcons were manufactured “and there’s only about 5,000 left”.

Just as it’s possible to build a replica Falcon GT, it is also possible to build a complete Vincent Black Shadow from new parts. The Vincent Owners Club have in fact done so (picture at left, web article here). In Australia, brothers Ken and Barry Horner are building and racing motorcycles with replica Vincent engines which they have named Irving-Vincent in homage to Phil Irving (picture below, website here).

The defining part in a build is naturally the engine case with its distinctive factory stamp. Record-keepers and Vincent spotters are quick to spot a fraud so non-genuine bikes are quickly identified and condemned as fakes.

Despite having little more than the skeleton of an engine, Andrew was able to tap into a rich vein of Vincent parts and knowledge that flows through Tasmania.

Together again

The knowledge came via Ray Andrieux, a well-known speedway sidecar racer who was no stranger to supercharged Vincent engines. Ray now lives in Tasmania and he took on the responsibility for rebuilding the engine.

A defining feature of the Black Shadow is in fact the black heart of the beast. The engine in Andrew’s bike has been finished in resplendent, deep black that is probably more glossy than the original stove-enamel paint but it sets the bike of beautifully and lets one know this machine is the business.

The bike draws people like moths to a flame. And so it should — the finish is first class.

Andrew’s efforts in locating the original engine are a reminder of what can be achieved with a bit of dedication and tenacity (and lots of cash too). He has resurrected a classic motorcycle that is a part of Tasmanian motor racing history and the result is simply stunning.

BACKGROUND

Don’t know much about Vincents? Here’s a dummy’s guide:

PHILLIP Vincent was a visionary who sought to introduce better handling and performing motorcycles to the world. In 1928, with the backing of his father, the 20-year-old mechanical sciences undergraduate purchased the HRD Motorcycle Company from its founder Howard Davies.

Vincent retained HRD identity and began to incorporate some of his designs, such as a revolutionary suspension systems, to their single cylinder machines. The factory progressed well under Vincent however the brand was let down by the J.A. Prestwhich (JAP) engines.

By 1931, Australian engineer Phil Irving had teamed up with Vincent and together they produced a 500cc engine which they named the ‘Meteor’. A more highly tuned unit followed and, in keeping with the theme, it was named the ‘Comet’. The Vincent HRD Company Ltd became a manufacture in its own right and a leader of innovation.

The crowning glory of the Vincent-Irving partnership was the V-twin engine that was developed in 1936 after Irving noticed how well two Comet blueprints looked together in the V-formation. The Series A Rapide was produced in a matter of weeks and was an immediate success.

Only 82 Series A machines were built. About 40 are known to exist in the world and they are now the most highly valued machines in the Vincent line-up, save for the Black Lightning: a 150-mph factory special of which 31 are known to have been produced. Series A Rapides and Black Lightning motorcycles are now commanding prices in the hundreds of thousands and will no doubt soon break through the million-dollar range.

After the war, Vincent returned to building high-quality, performance motorcycles with the release of his Series B line-up. The name ‘Rapide’ was carried over for entry-level V-twins, but Vincent had some surprises in store.

Released in 1948, and sitting between the Rapide and Black Lightning was the Black Shadow, a factory hot-rod that has generated a legend that is possibly larger than the machine.

Vincent Black Shadows are highly desirable, highly collectable and sought-after motorcycles. From an Australian perspective, think of them as the Falcon GTHO of the motorcycle world.

Also see:

The world’s best Vincent collection — in Western Australia! Click here.

The world’s best Vincent collection — in Western Australia! Click here.

Earl Davey-Milne, who ran with Doug Whiteford in the day, also reports he knows of no such connection for Doug, but that there was a Ted Whiteford, sometimes confused with Doug, who ran a “Whiteford Special” (details unknown).

Further to my previous comments, I own the only hill climb supercharged Vincent known to carry the Irving name. The Cooper-Irving developed by Phil for Lex Davison and winner of the Australian Hillclimb Championship at Albany in 1958.

Re-Whiteford/Irving relationship. This was fractious at best, following work reluctantly done by Phil designing a limited slip diff commissioned by Doug for the Lago Talbot which, as Phil had warned, immediately failed.

Doubt Doug Whiteford had any connection with “Whitford (or Whiteford)-Irving” car described or indeed any air-cooled car, confirmed with several who raced with him in the day. He climbed the Kaye Special (V8 Lincoln) and occasionally period sports cars (Triumph TR2 and Austin Healey 100S.