Tags: Buy classic motorcycles, buying used motorcycles

Nine questions you must ask if you’re buying a used motorcycle

In the market to buy a used motorbike? Whether you’re buying modern or classic, sports or touring, British, Japanese or European, here are nine questions you need to ask (and answer) before you hand over your hard-earned cash.

Question 1: Has it been stolen?

This is the biggest risk in buying a used motorbike, but it’s usually easy to establish. Remember, a stolen motorcycle always belongs to the person from whom it was stolen. Yep, even if you’ve paid (a thief) good money for it, and even if they paid (a thief) good money for it.

Licensed bikes

If you’re looking to buy a classic motorbike that is already licensed, you want to see two things: some formal identification of the seller (such as their driver’s licence) and the motorcycle’s registration papers. While you have the rego papers in hand, check to make sure the bike’s engine (or frame or VIN) number is the same on the paperwork as it is on the actual bike.

If the bike is licensed in the name of the person you are buying it from, you’re good to go. If that’s not the case, tell the seller “that’s a problem” and they need to convince you that the bike isn’t stolen. If they can’t, or their answers sound dodgy, walk away.

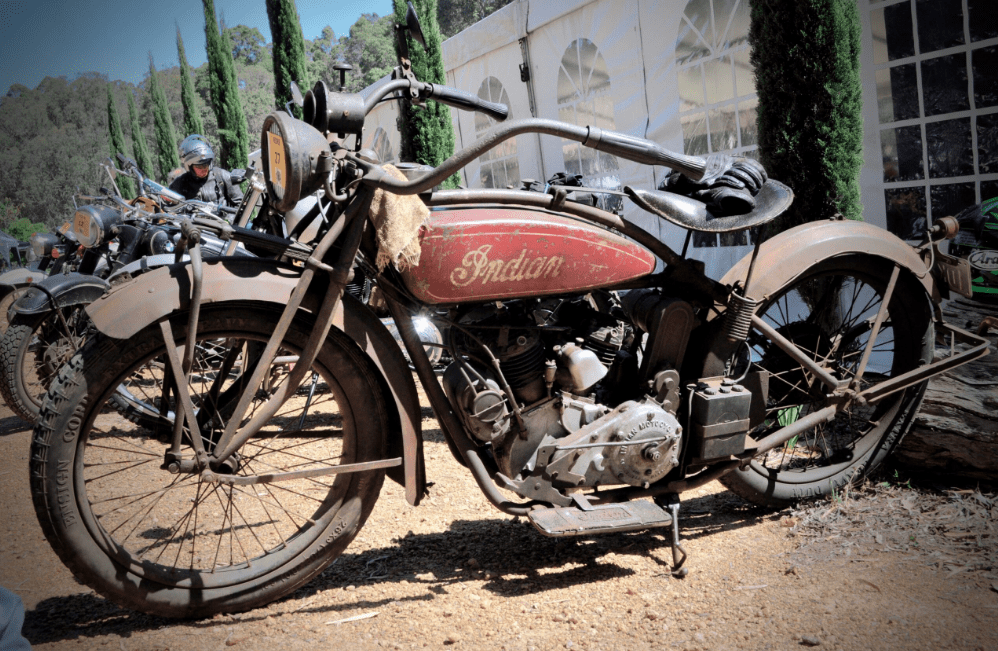

Unlicensed (but previously licensed) bikes

If you’re looking to buy a classic motorbike that is unlicensed but has been licensed in the past, the seller should have the old paperwork. Paperwork lost, stolen, or eaten by the dog? Hmmm. When you try to get the bike licensed, your local licensing authority will want to be confident it hasn’t been stolen (either by you, or the person you bought it from, or indeed the person they bought it from), and see evidence of ownership. You will want a receipt when you buy, but you will also want a paper trail reaching into the past. If the trail doesn’t connect to a person who owned it and had it registered, you are exposed to some risk.

I had some nervous moments recently when I bought an old BMW that had been off the road for 20 years, and had changed hands several times as a chattel in a farm shed. The original owner was long dead, and any papers long-lost. The clouds dispersed and my world got simple when the bike’s old licence plate showed up. The authorities were able to match the plate with the engine number in official records, and my story stacked up. I’m not sure what would have happened if we’d not tracked down the plate, but it might have got ugly.

Never-licensed bikes

If the bike has never been licensed and never will be licensed (off-road bikes, for example), you need to convince yourself that you’re not buying from a crook (or someone who bought it from a crook). As I said earlier, a stolen bike always belongs to the person it was stolen from — and you don’t want the long arm of the law taking it away from you. (You also don’t want to reward bike thieves by doing business with them, right?)

Start by asking the bike’s history — how long have they owned it, where did they buy it etc. Then ask some questions to expose a non-bike person. What fuel does it take? What oil? Where do you get it serviced? Just poke and prod with some simple questions, and you’ll get a gut feeling whether all is above board. If you get: “I dunno. I’m selling it for a mate of mine”, reply “yeah, sure you are” and walk away. Maybe call the cops too, just for fun.

Another quick check is to eyeball the bike’s frame number and engine numbers. If they’ve been removed, there have been fraudulent shenanigans. Walk away.

Question 2: Is it genuine?

If you frequently buy classic motorcycles, you should know all about this one.

A collector I know tried to sell a rare and valuable Vincent motorcycle a few years ago. There was a lot of interest from all over the world, but eventually a deal was done subject to some basic due diligence. And guess what? When the would-be buyer ran the bike’s engine and frame number through the Vincent Owner’s Club in Britain, he found there was a bike in London with the same frame number. Uh-oh. In the world of rare and valuable motorcycles, a fake frame number is serious stuff. Somewhere in the bike’s 60-odd year history, it’s engine and frame parted ways — and someone knowingly covered it up.

Needless to say, the gonna-be buyer cancelled the sale. The tale had a kinda-happy ending, at least for our seller. He was still in contact with the person he bought it from several years earlier, and that person agreed to buy it back at an agreeable price (denying any knowledge of the fraud).

What’s the lesson? If originality is important, and impacts the value of the bike, then do what the buyer in my tale did — make an offer subject to due diligence, then do some research using the bike’s engine and frame number before you take possession and before you hand over the cash, other than a reasonable deposit.

Once you have the engine and frame number (and licence plate if it has one), an hour or two on the internet will reveal whether the frame and engine belong together, what the bike is, what year it was built, and its registration history. If you can find a club or other source of specific expertise, you might also find details of previous owners and the name of the shop that sold it new.

Question 3: Is it about to blow up?

Well, does it sound like it’s about to blow up? If it starts okay, runs okay, doesn’t blow huge amounts of smoke, and goes and stops like it should, then it probably is okay. Listen for weird noises and look for smoke and oil. Keep in mind a bit of smoke and oil never hurt anyone, within reason. (My Ducati needs a healthy dose of choke to start, and the rich mixture generates a puff of smoke on start-up. I also have a 1972 Triumph Bonneville and if it’s not leaking any oil, I reckon it’s run out.)

If you don’t have the expertise to know a weird (expensive) noise from a normal noise, find someone who does and take them with you. But as a starting point, expensive noises are usually loud … clunk rather than tick, if you know what I mean.

If the bike has been serviced or had any repairs done recently, the seller should be willing to tell you where the work was done. A visit or phone-call to the bike shop can give you confidence. I have done this when buying bikes from inter-State, and once when considering a bike on the other side of the world. Both times the shop was perfectly happy to talk to me. (No problems, as it turned out, either time.)

If you really like the bike but have some doubts, put it to the seller straight up — “If this thing blows up in the next week can I bring it back?” It’s a fair request, and most sellers will agree. I have bought and sold bikes with that “seven-day verbal warranty”.

If the bike won’t start or can’t be ridden (dead battery, broken chain or whatever), the price should be way lower than a runner to allow for unseen expenses. And the short-term verbal warranty might best be written down. And signed.

Question 4: Will it be a money pit?

That depends. If it’s licensed and running fine, and you leave it alone, all should be well. If it’s running poorly, if forks, wheels and swinging arm make funny clunk noises when you wobble them, or if the engine is in bits (or in a box), then you’ve not bought a motorbike, you’ve bought an expensive ticket in a lucky dip. You’ll have a lot of fun. Especially if you’re single, and/or you are one of Rupert Murdoch’s kids.

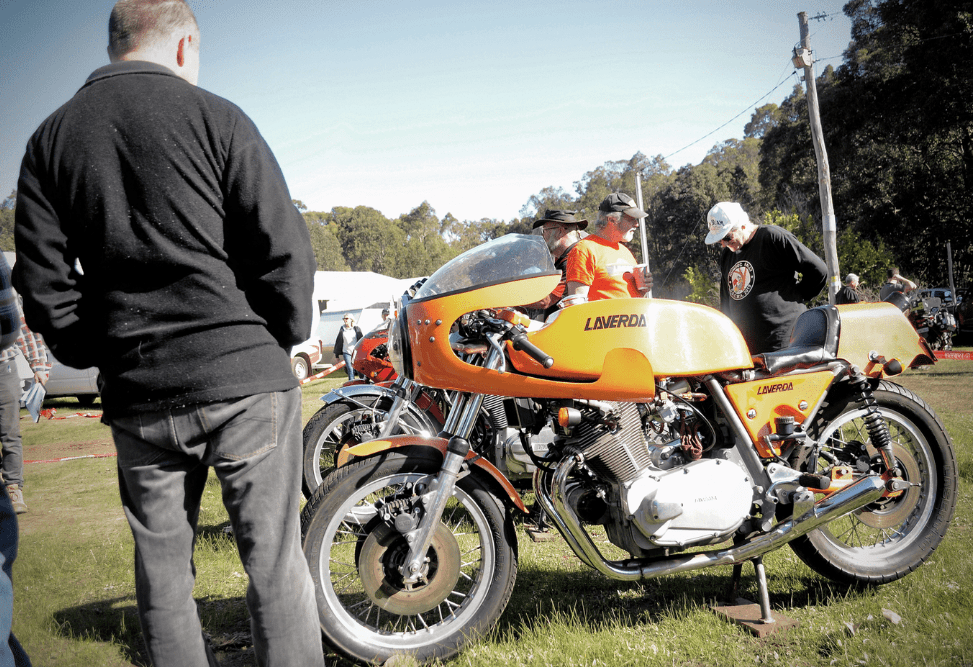

Near-new bikes are usually sale from this risk, but if you buy classic motorcycles then you are entering the territory of potentially expensive discoveries.

The two biggest “money pit” risks are buying a motorbike that needs expensive parts (ie difficult or impossible-to-find), and/or one that needs work involving specialist expertise you’ll need to pay for. I can pull a frame and engine to pieces and put them back together again, usually in the right order. (More or less.) I can also clean, scrub, polish, sand, putty and paint. These skills have reduced the depth of several money pits I have acquired over the years. But I can’t weld, I don’t own a lathe or milling machine, and I can’t conjure up an original set of mufflers for a 1969 Honda CB750 or a NOS petrol tank for an MV Agusta 750S.

If the bike needs a lot of work and there are key parts missing, don’t buy it without first doing some quick research. Once again, we’re only talking an hour or two on the ‘net. Make a quick list of what appears to be needed (especially parts) and then ask Mr Google if he can find them for sale — and how much please?

And while you’re sitting behind the computer, find some relevant Facebook groups and ask “what should I look out for?” You’ll get a couple of dozen conflicting answers in ten minutes, and you’ll start an online brawl that will run for a fortnight. All good clean 21st Century fun.

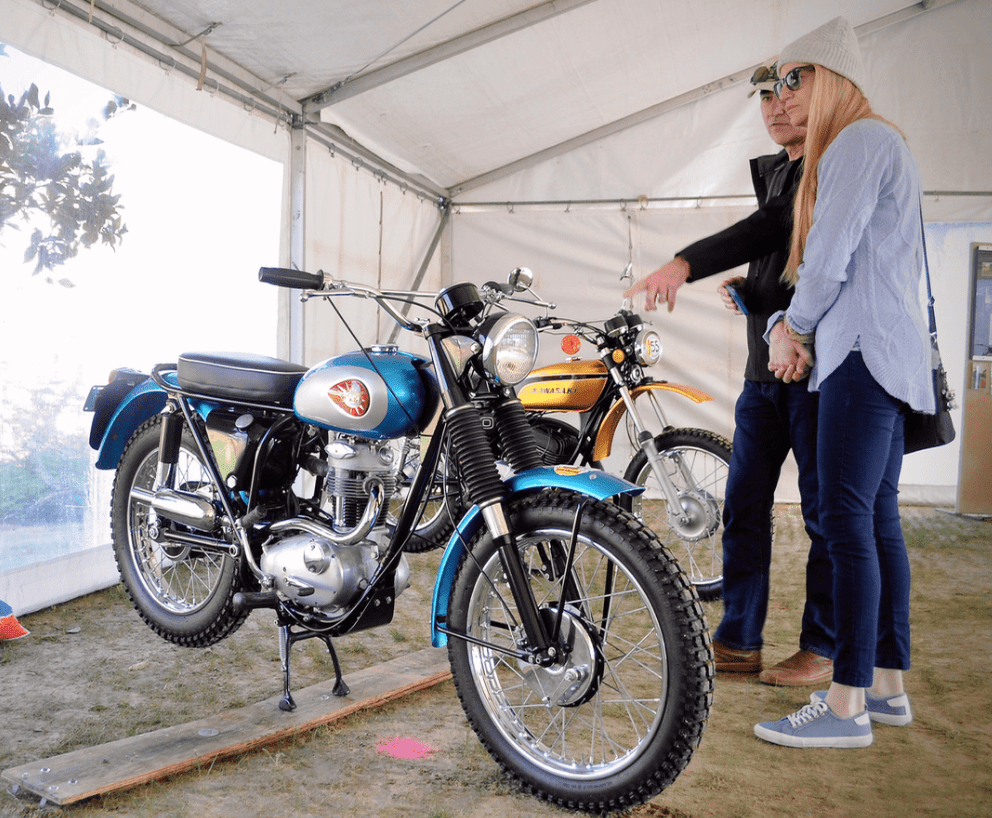

Question 5: Am I paying too much?

It’s really not very hard. Do your research. Ask Mr Google to find examples of that bike for sale, anywhere in the world. And Google will find some. A client recently asked me if I could give him any idea of the market value for a grey-frame 1971 BSA Rocket 3. I’d never heard of one. Turns out only 200 were ever made. “Cripes,” I thought. “I wouldn’t have a clue!” Ten minutes later, I found one had sold, three days earlier, at an auction in London. I know London isn’t Brisbane, but it was genuine, honest, useable market intelligence.

Having said that, when you ask Google, do be sure to seek exactly the same bike — as in same year, same model, same level of spec — and you can then make some allowance for condition. Original engine and original paint add value, but being worn out detracts value. If thoroughly rebuilt examples are on the market at $20k, and original low-mileage ones are asking $25k, then your tired example that Madge painted with red house paint is not worth $30k. The science doesn’t need to be precise, hey. It’s just the vibe. And keep in mind asking prices are almost always higher than selling prices. Allow 10%.

Question 6: Has it been looked after?

Motorbikes are tough machines. They really are. We can treat them poorly and they just keep on going and going and going. Until they stop.

Point is, unless you’re looking at the very last green-frame Ducati 750 SuperSport on earth, you don’t actually have to buy this particular bike, do you? There will be another one, very similar, listed on The Bike Shed Times any day now. So, don’t buy one that hasn’t been looked after. Because if the engine oil hasn’t been changed reasonably often (and the fork oil, and transmission oil) and if it hasn’t been washed occasionally to keep rust at bay from the exhaust and frame components, the bike is going to wear out much faster than one that’s been kept clean and in fresh lubricants.

How can you tell? Easy. “Hey cobber, when did you last change the oil, and what oil did you use?”

Quite honestly, that’s all you need to ask. The seller will either answer your question with credible confidence, or he won’t. If he says he has never changed the oil and wouldn’t have a clue when or what, that’s kinda good news because you’re doing business with an honest person. (Possibly a twit, but at least an honest one.)

If he tries to tell you an outright lie, his voice will stumble and you’ll see it in his eyes.

Hopefully, he’ll either generate a detailed receipt and workshop report from the bike’s last service (check the date), or he’ll point at the half-empty oil container in the corner of the shed and say he changed the oil last month, and the fork oil last September. If he changes the oil every year (hey, even every two), then chances are the bike has had enough love to keep it alive for a long time to come.

Question 7: Does it need anything soon?

Just look at it. If the chain is rusty, the sprockets hooked, the tyres bald, then yes. You’ll need to replace them. If the rego is about to expire, you’ll need to do that. Duh.

And don’t be shy in asking the question. “Does it need anything soon?” People might not volunteer negative facts about the bike they’re trying to sell, but it’s quite a rare schmuck who can actually tell a bald-faced lie, face to face. Put them to the test. But take a look at it, too, hey?

Question 8: Will it do the job?

Make sure you’re buying the correct bike for your purpose. Don’t laugh, this is serious. If you want a bike to ride to work and back, in traffic, stopping at the lights and such, don’t buy a 200hp sports bike. It’ll drive you mad. It’ll stall all the time, it’ll refuse to find neutral, and it will probably overheat. Buy a Vespa. Or a (modern) Triumph Bonneville. Or maybe buy an old classic motorcycle, but only if it’s in tip-top shape.

Equally, if all your mates have R6 Yamahas and Triumph Speed Triples, and you plan to join them on weekends to see how many of you can reach 35 (years that is, not miles per hour), then you should probably get something similar. Just make sure that your feet can reach the ground, your hands can reach the bars, and your knees can reach the tarmac, preferably all at the same time in, er, comfort. And also that you have top hospital cover and life insurance.

Take the bike for a decent ride before you hand over the cash. I once owned a BMW K1300R. It was a wonderful machine. Unbelievably fast, comfortable seat, quality kit, good luggage, pillion-friendly. But it hurt my wrists after 10km. Agony. The guy I sold it to, loved it and had no wrist problem at all. Try before you buy, even if that’s only 15 minutes.

Question 9: Do you trust the seller?

You know what? You can almost ignore the previous eight questions if you can answer ‘yes’ to this one.

If the seller is credible, relaxed, answers your questions honestly and without hesitation, you’re almost certainly on safe ground.

If not, buyer beware.

Good luck!