Originally published August 2018.

THE BSA Rocket 3 could be seen as the bike that killed the British motorcycle industry. In 1966, Triumph was ready to release the three-cylinder Trident Triumph. It could have been — should have been — the world’s first superbike. But Triumph’s siamese-twin company BSA said it wanted a triple too — and it wanted Triumph to postpone the release of Trident until the almost identical BSA Rocket 3 was ready. It was a decision that cost both companies dearly; while they naffed around, Honda released the 750/4 in 1969 and stole the motorcycling world’s imagination — and a dominant market share that Japan has held ever since. DAN TALBOT reports.

AS A young bloke growing up on a farm, I was lucky enough to own a BSA although, sadly, not of the motorcycle kind.

My product of the Birmingham Small Arms Company was a small arm, namely a 0.177 calibre air rifle. My air rifle was not the most powerful weapon around but, for a long time, it was my most prized possession.

BSA, as the name suggests, started out manufacturing firearms before moving into bicycles and then the motorcycle. Defence contracts during the war years helped strengthen the company setting it up to become a motorcycle empire within the Empire. Unfortunately empires can come crumbling down and BSA would be no exception, about the time Dad was handing me my first (and only) rifle, BSA was basically in ruins.

Outside of the human variety, my first great love has always been motorcycles. It started in the first decade of my life and blossomed unabated through my teens, adolescence and adulthood. My introduction to motorcycles came via our farm bikes and Dad’s competition enduro machines. On Sundays Dad would drop me at the local motocross track and I would be glued to the fence watching brave men wrestle powerful machines though the dirt and long for the day I would get my opportunity to join them.

At 16 I left school and secured an apprenticeship. It paid a meagre wage but it was enough to finally realise the dream of becoming a motorcycle racer. In the 1970s competition machinery was largely of the two-stroke, Japanese variety, and I had my eye set firmly on the 250cc class. European machinery was popular but way out of my price range and British bikes were nowhere to be seen in Australian dirt bike racing.

Of course, I was well aware of BSA motorcycles long before I obtained my air rifle, but they were known mainly as old bikes that cluttered sheds and garages (including our own). The only BSAs that seemed to be running back in the 1970s were Bantams, a rudimentary 125cc 2-stroke that had been relegated to paddock hacks by the time I even learned they existed.

The fact my air rifle carried the famous winged BSA emblem was not completely lost on me and I took more than a little pride in owning a fine piece of equipment, although barely a thought was given to ever owning an actual BSA motorcycle.

I know now there were larger capacity BSA machines running around on the roads, the survivors bear testament to that, but they were few and far between. By 1969 the Honda 750 four had made its debut and the Kawasaki 900 followed soon after. These two superbikes basically confined British machinery to history, or so it seemed. The big Japanese multi-cylinder bikes quickly gained a reputation for speed and power. They looked large and purposeful. My mates and I were hooked.

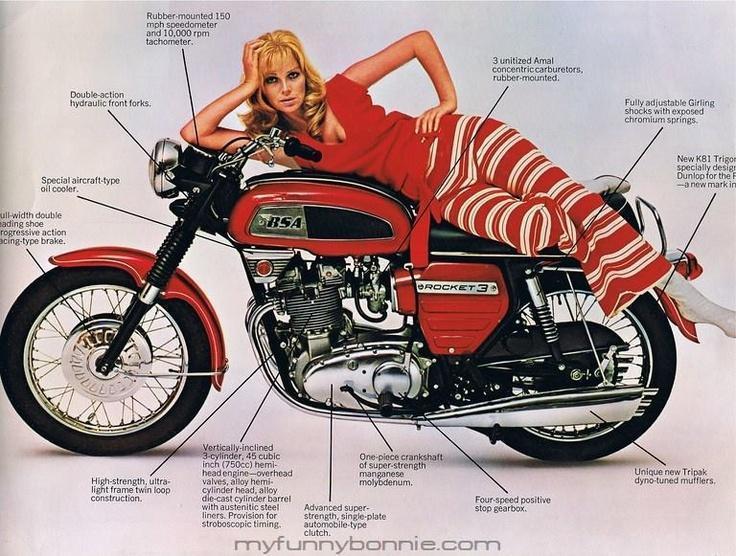

Shortly before the release of the Honda Four (as it became known), BSA were releasing their own multi-cylinder machine, the 750 Rocket 3, which, strangely enough, is a triple. The engine proved to be beauty, a world-beater – despite the use of older technologies.

The Honda had an overhead camshaft engine in an evil handling frame, whilst the BSA used the older style, less powerful, push-rod engine in a sturdy, sure footed frame. This was a last-ditch effort by BSA to reclaim their place in history. Sadly, it was destined to fail — but due in no part to the machine.

Procrastination and a need to stand apart from their sister machine, the Triumph Trident, would see the demise of the once great motorcycle manufacturer. In hindsight, the British triples were destined to be lost in a tsunami of reliable, gleaming superbikes out of Japan but things could have been different. They could have had the jump on Honda by about three years if only they had stuck with badge-engineering, as opposed to re-engineering. Long before the triple cylinder engine was even thought about, BSA subsumed (think of consumed but eating money instead of food) the Triumph name. But the two entities remained separated – kind of.

Procrastination and a need to stand apart from their sister machine, the Triumph Trident, would see the demise of the once great motorcycle manufacturer. In hindsight, the British triples were destined to be lost in a tsunami of reliable, gleaming superbikes out of Japan but things could have been different. They could have had the jump on Honda by about three years if only they had stuck with badge-engineering, as opposed to re-engineering. Long before the triple cylinder engine was even thought about, BSA subsumed (think of consumed but eating money instead of food) the Triumph name. But the two entities remained separated – kind of.

The three-cylinder engine had been in planning and design for almost nine years before its release. Triumph engineers Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele were the fathers of the triple. Singles and twins were common place in the British industry but there was a growing demand for faster and more powerful machines, particularly to feed the demand from America. This presented a problem. The larger and more powerful twins became, the larger and more pronounced the vibration became. In hindsight, the progression from single to twin to triple seems logical, but it took Hopwood and Hele to bring it to fruition.

In 1960, vibration was an accepted by-product of the internal combustion engine but Hopwood and Hele, quite rightly, realised the motorcycle riding public would eventually demand smoother running engines. The automobile world had proven that. Their design brief was to spread the power and vibration between 120 degree firing intervals, instead of the 360 cycle the twins were using. It was radical, revolutionary and audacious; traits that had enabled the British motorcycle industry to rule the world up until that time.

Throughout its development, the three-cylinder engine was destined for the all new, aptly named, Triumph Trident. But a decision verging on last minute was undertaken to release the machine under both BSA and Triumph brands, which were obviously held by the parent company named BSA-Triumph.

The Triumph prototype was completed in 1965 and the Trident could well have gone into production by 1966, had BSA not wanted part of the action. Not content with badge-engineering, BSA insisted on making a triple of their own and this is where things get a little ridiculous. The Triumph triple cylinder engine was built in the BSA factory at Small Heath. It was, for all intents and purposes, a BSA engine. In following naming conventions of the day, engines destined for Triumph were stamped with the prefix T150. BSA engines were stamped A75. That’s easy, no problem there, except to see the difference between the engine prefixes one almost needs to get down on the ground to read the stampings.

It was decided the BSA engine would need a distinctive look so the barrels on the BSA unit were canted forward by 12 degrees, which, kind of, dissociate them from Triumph. The right side timing and gearbox outer cases were also altered to provide another individual touch to the BSA item. Think of designing something that is basically the same yet requires re-tooling, casting, machining etc and the simple act of making minor changes becomes a major undertaking. Luckily, the internals remained the same between the two engines, as did just about every other piece of the triple.

With the engine (almost) uniquely styled to BSA, it became apparent the Triumph duplex frame would not support the forwarded slanting engine — so the BSA would need a new frame too. Conveniently, Triumph would later use the same set up to allow inclusion of an electric start behind the barrels of their 1975 T160.

The finished product would add two years to the release of both bikes and BSA-Triumph missed the opportunity to unleash the first mass-produced superbike onto the world market. Honda stole the show. The Brits had been caught resting upon their laurels. They were the motorcycle super-power of the time and probably expected to remain as such.

The three-cylinder engine proved to be a gem but it was cloaked in a tradition of clunky, solid and not altogether reliable motorcycles. By contrast, Japanese engineering was proving to be capable, efficient and bullet-proof. However, the Oriental frames were a weak-point. In the years following their release, bespoke frame-builders would offer alternative items for both the Honda Four and Kawasaki 900. In the meantime BSA and Triumph took to the race tracks with great success. Clearly the engine was a winner but the bikes failed to meet sales expectations.

According to some pundits, the BSA and Trident failed the styling test. It completely missed the mark with its bread-box tank, dinner-plate side panels and hideous “ray-gun” exhausts (ironically, ray-gun mufflers are now highly sort after by modern-day collectors).

Advertisements with attractive models draped over the bikes failed to dull the impact the Japanese were having. Triumph were winning production racing around the world, including the two most famous races of the time, the Isle of Man and Daytona. BSA dominated the American AMA competition well into the 70s but sales of the Japanese bikes soared, while sales of the British machines stagnated.

The bikes generally remained the proclivity of purists both then and now. With fewer bikes produced, BSAs command higher prices, which leaves Tridents as representing excellent value for money in classic motorcycling collecting.

So where’s all this leading? Well, in my search for a Trident, I uncovered a gem in the form of a ’71 Rocket 3. It is a basket-case but it’s all there. And it’s the more appealable Mark II, American-styled BSA, rather than the boxy English design by David Ogle, who was more accustomed to designing radios, toasters and a thoroughly awful car.

I will soon begin to bring the pile of dusty, rusty parts back to life with my mantra of painting, plating or polishing every surface of the machine. Moving parts will be assessed and, if need, replaced. Unless it’s in exceptional condition (which is unlikely), the 4 speed gear box will likely be tossed in favour of a new “Quaife” 5 speed transmission.

My nipples are busting in anticipation!

Another excellent read. Many thanks – again. Having been raised on a diet of “British is best”, any articles about “Pommy” bikes are always welcome. However, the need for a catchy article title notwithstanding, I have a bit of an issue with the claim that one bad decision by BSA/Triumph in 1966 resulted in the decimation of the British motorcycle industry.

Throughout the drawn-out collapse of the industry, there was a whole bunch of factors at play, and the writing was on the wall long before the Trident/Rocket 3 debacle; that was more of a symptom of the malaise rather than the cause. Despite the success of the Brit bike industry up to the sixties, behind the headlines they were busily engineering their own demise from the immediate post-war period onwards. Poor management, poor funding, poor/dated design, poor marketing, poor materials and quality control, poor reliability; the list goes on and on. And all hidden behind the facade of racing success, and the mantra “What wins on Sunday, sells on Monday”.

Arguably, by focusing almost exclusively on performance bikes, instead of a range of machines which catered to non-traditional motorcyclists as well as enthusiasts (which is exactly what Honda did), the Brit industry effectively denied themselves a market which could have kept most (or at least many) manufacturers viable. It is interesting to note that the highest selling British motorcycle in history is the humble BSA Bantam; ‘stolen’ from DKW post-WW II and left virtually unchanged throughout its production life, it was one of the only bikes to consistently turn a profit for BSA. In retrospect, one has to wonder why every company didn’t have at least one “bread and butter” model like the Bantam on the market to provide a steady income – if only to support the “glamour” end of the business. Cotton, Francis Barnett, James, etc? These were hardly a serious attempt to cater to the non-traditional motorcyclist and offered no real (or better) alternative to the offerings of the larger players.

This failure to cater to a broader market was the door which was left wide open for the Japanese, (and to a lesser degree Italians with the Vespas and Lambrettas) to walk right in and capitalise on a world market just gagging for cheap, reliable transport solutions. Through this, the Japanese invasion was well underway long before the release of the Honda CB750 Four. That was just the final nail in the coffin of the Brit bike industry.

Before I step down from my soap box, as an aficionado of Brit bikes, I must recommend the book “The Strange Death of the British Motor Cycle Industry” by Steve Koerner. This book is a few years old now (2012), but is still one of the best analyses of the Brit motorcycle industry I have read – ever. There is a very good review here https://gregwilliams.ca/1779/ but if you can get a hold of a copy, it is a cracking good read from cover to cover whether you are a Brit bike tragic or not.

It doesn’t always arrive, but there’s a Rocket 3 that races with Western Australia’s Historic Competition Motorcycle Club. Come to Collie some time and hear one ridden in anger.

Great reading, brought back a few memories and things I had forgotten.

I remember seeing Murray Ekersley on an American model Rocket 3, beautiful looks and sound. Thankyou Dan.