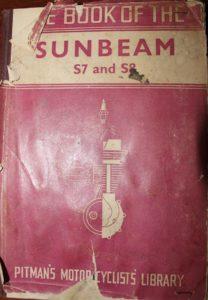

“A civilised motorcycle of almost enchanting appearance, with remarkably smooth and lively performance, genuine mechanical silence and exceptionally good reliability, a machine which neither discomforts nor dirties the rider, nor calls upon him to devote excessive spare time to maintenance (W.C. Haycraft, Pitman’s Book of the Sunbeam, 1954).”

ALMOST enchanting? W.C. Haycraft, or WCH as he preferred, was writing the preface for Pitman’s Book of the Sunbeam and was clearly very excited about the Sunbeam twin. He congratulated owners on their choice of machine, saying: “Few modern luxury-type motorcycles have made such a well-merited and rapid climb to stardom and popularity.”

BSA purchased Sunbeam during the post-war manufacturing boom as a vehicle to break into the luxury end of the motorcycle market, something akin to Toyota’s Lexus brand. As a single-cylinder motorcycle, Sunbeam was bounced around various manufactures, including Matchless and AJS, but, all the while, maintained a reputation for quality and sophistication.

When BSA acquired the company they promoted Sunbeam as their gentleman’s line of motorcycle with the promise of a new 500 twin that would project the company into the luxury end of the post-war motorcycle world, similar to the position once enjoyed by Brough Superior.

When it arrived in 1949, the 500 twin was an audacious, quirky creation that has been described as an odd mixture of the inspired and the impractical. A hefty price tag and modest performance resulted in modest sales but Sunbeam pushed on surviving for a decade within the BSA empire. The motorcycle underwent very little development during its run and, in 1956, the machine was put out to pasture. In hindsight, the reason for its demise is as clear as an English Spring morning.

Writing in Classic British Motorcycles in 1996, Roland Brown described early examples of the bike as being underpowered and beset by terrible vibrations and poor handling. This is a generally accepted description of the early S7 machines but many of the problems were later rectified or improved in the models which followed.

Around the time Roland Brown was penning his article on Sunbeams, I was restoring a BMW R80. It was my second go at rebuilding a motorcycle and was an excellent choice, not least because the restoration required little more than a paint job and minor engine rebuild. In dismantling that bike I was struck by the synchronicity of the design and I’m sure anyone who has ever worked on a boxer twin will agree that it is a brilliantly thought out motorcycle. Picture the crankshaft lying longitudinally with the frame, spinning though a single-plate clutch, a robust gear box and a shaft driving a bevel pinion gear. The result is a simple, harmonious and effective driveline that has stood the test of time.

In a clear case of imitation is the best form of flattery, the design has been emulated by the Soviets, the Chinese and even the Americans with their 1942 Harley Davidson XA, of which some 1000 units were produced. The sturdy, purposeful nature of the BMW design was not lost on the British either.

The 500 Sunbeam twin is unashamedly modelled on the BMW R75. The crank lies parallel to the frame, driving through a single-plate (and very heavy) clutch, a shaft and worm-drive differential. Folklore records the Sunbeam being copied from an R75 that was captured during World War II. This is probably a romantic notion. Erling Poppe, the designer of the Sunbeam twin, was Austrian by birth and German technology would not have been lost on the young engineer.

To back-track a little, from 1912 Sunbeam Cycles Ltd forged a solid reputation on both road and track. They were in the vanguard of innovation and invention that earned the British motorcycle industry a reputation as leaders in the field. The single-cylinder Sunbeam motorcycles were able to project dual personalities of both sports bike and gentleman’s motorcycle but natural progression was leading in one direction – young men wanted to ride fast bikes and twin cylinder motorcycles were the obvious answer.

Arguably, with Edward Turner’s revolutionary Speed-twin engine, Triumph were the winners here. Turner was ahead of the play having almost 10 years of development before the Sunbeam twin would emerge. Whilst Vincent was the undisputed king, Triumph were building affordable, obtainable bikes that spawned generations of young dare-devils.

Sunbeam realised to keep pace with the opposition they would need a twin and Poppe was commissioned to build it. Poppe came up with an amalgam of the British parallel twin and the German boxer set up with the latter design having emphasis upon the drive train. The engine is cumbersome which necessitates the longitudinal arrangement. With huge sand-cast casings, one would expect the engine would lend itself easily to increased cubic capacity.

As it was, Poppe’s layout unleashed considerable vibration beyond what the British and German designs were known for.

The bikes were nonetheless released for sale — but the buying public were having none of it and the machines were quickly recalled and fitted with rubber engine mounts. The modification was successful.

Depending on the speed of the engine, the result is somewhere between a manageable shake to a pleasant hum. The S7 hit the market with 16-inch wheels, looking all the world like a WLA Harley had slept with a BMW and produced a bastard love-child that only a mother could love. The wide tyres and torque effect apparently make the S7 a bit of a handful to ride but with around 2500 units produced, and despite its beefy appearance and discordant mechanics, the S7 has become the pick of the Sunbeam bunch and now enjoys something near cult status.

In 1949 the new, improved S8 was touted as a sportier version of the machine, with its conventional sized wheels and increased horsepower from 24 to 25. With the bulbous fats gone riders put that extra horsepower to work and attempted to transform the gentleman’s motorcycle to a sports bike, with disastrous consequences.

Stewart Engineering who today supply or produce most parts for Sunbeam motorcycles, described the S8 as “producing too much brake horsepower for the wellbeing of the components.”

Research and development of the time dictated that a bevel final drive was the best option for power transmission. The Germans had proved it, everyone knew it. Nevertheless, Sunbeam chose a bronze worm-drive unit because they happened to be in possession of machinery which cut worm-drives, not bevel gears. When the power of the 500cc engine was lifted by improved camshaft profiles and increased compression the bikes began stripping the worm-drive.

Astonishingly, having been identified as the ideal police motorcycle, instead of improving the final drive, the fix was to detune the engine. Cops will thrash whatever vehicle they are given to within an inch of its life (trust me, I know). It is a good test of machine and, evidently, the Sunbeam was not up to the task. Had Sunbeam taken the logical choice and beefed up the final drive they may have seen a brighter future.

Of course, now days, any weakness in the much-loved Sunbeam is furiously disputed by modern-day owners of the marque who claim regular changing of the differential oil rectifies the problem.

Make no mistake, a well-sorted Sunbeam motorcycle is a joy to ride. The S8 in the accompanying photographs used to be mine. Starting it was easy. In fact, I used to be able to ‘kick-start’ the engine by hand. The engine would bounce around on its rubber mounts and chug happily away like an old water-pump.

It’s easy to imagine how the young guns of the 1950s would strip the worm-drive through less than judicious use of the power although, like other bikes of the era, the Sunbeam doesn’t inspire hard riding. Braking is almost non-existent and cornering consists basically of tip in, wrestle the slow steering, accept a poorly suspended frame, all the while bouncing around on huge twin chrome springs which held the saddle above the rear guard. Things would generally turn out okay although exiting a corner sometimes came first as a surprise then a relief.

It’s easy to imagine how the young guns of the 1950s would strip the worm-drive through less than judicious use of the power although, like other bikes of the era, the Sunbeam doesn’t inspire hard riding. Braking is almost non-existent and cornering consists basically of tip in, wrestle the slow steering, accept a poorly suspended frame, all the while bouncing around on huge twin chrome springs which held the saddle above the rear guard. Things would generally turn out okay although exiting a corner sometimes came first as a surprise then a relief.

The tone which came from the Sunbeam twin was not unlike that which comes from the wife’s 865 Bonneville engine. Both bikes have factory exhaust systems, the large cast-iron Sunbeam item is a survivor of the ’50s and it allowed enough decibels to escape to let me know it’s connected to a British twin.

I fitted my bike with an electronic ignition unit and redundant spark setup which allowed me to ditch the old car-style distributor. I understand this is bending the rules of classic bike ownership but I wanted the engine to run clean and long (it didn’t, but anyway …).

In the 1940s Sunbeam heralded a bright future for the British motorcycle industry. The twin was destined to become a gentleman’s machine and promoted with terms associated with comfort and luxury. It could have been more successful, indeed it should have been. The British were well on their way to producing a viable competitor to BMW but, it would seem, the public were not ready to receive such an unusual machine. Surprising really as W. C. Haycraft was quite taken with it.

For a final word on this, the most civilised of motorcycles, we shall hear one last quote from WCH:

“You possess a machine which delights the eye, is easy to handle and a revelation to ride.”

Quite right, my good sir.

Learn more abut the Sunbeam twins here.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Enjoy our work? You can help by Liking or Sharing on Facebook (there’s a button below) or Subscribing to our website (top right). Thanks.