DAN TALBOT has finally got his hands on a Triton, without butchering his dad’s old Thunderbird. It’s precious metal.

BACK in the days before fibreglass and plastic, the top choice in lightweight materials for racing and specialist manufacturers was aluminium and alloy.

In post-World War II Britain, Jaguar, AC Shelby and Norton all produced exotic beauties handcrafted in aluminium and alloy. Less well known, in Australia at least, was the stunning line of ‘Airstream’ caravans out of America.

The Airstream was designed in the 1930s by Hawley Bowlus, an engineer, artisan and close associate of aviator (and serial polygamist) Charles Lindenbergh. Bowlus saw a potential commercial use for left-over aluminium parts from the aviation industry, and the Airstream – a cross between an aircraft and a motorhome — was born.

Meanwhile, on the other side of The Pond, things were heating up in the motorcycle industry. The British set about reaffirming their place at the top of two-wheeled motorsport, but first they had to win at home — and the machine designed to do it was the 500cc Manx Norton.

The Manx engine was a ripper, but by the late 1940s Norton recognised they needed a better frame. Specialist frame-building brothers Rex and Cromie McCandless were engaged by the company and set about developing a frame specifically for the Isle of Man circuit.

The new bike made its debut in 1950, whereupon Norton works rider Harold Daniell declared the new frame was “like being on a feather bed”. Ever since, Norton’s double-cradle, welded steel frame has been known as the Featherbed. Manx Nortons finished first, second and third in the 1950 TT (and Harold finished fifth). The die was cast. Norton would dominate the mountain circuit for the next five years and the Featherbed frame was destined to become an icon.

Norton’s winning reputation wasn’t lost on the four-wheeled racing fraternity. Manx engines increasingly found their way into Formula 3 open-wheeler class racing cars. But Norton wouldn’t sell the engines on their own — so for every Manx-powered racing car that was built, a chassis was pushed aside.

Just as Bowlus recognised an opportunity to use all those left-over plane parts, giving birth to the Airstream, so some enterprising person could see value in those surplus Featherbed chassis. A big Triumph twin engine in one hand, a Norton chassis in the other, and the Triton was born.

The bike featured here is not one of those early machines. It is a modern-day re-creation built, like the Airstream, from off-cuts and parts; a meeting of old alloy and modern steel.

While the Triton was founded on mid-20th Century parts-bin specials, there has been a renaissance — and specialist manufactures are turning out what are essentially new bikes. ‘Made in Metal’ is one manufacturer worth having a look at for some very nice machinery. Elsewhere, in the ultimate testament to the enduring nature of an almost 70 year-old design, some people are putting modern Hinckley Triumph twins into Featherbed frames.

The Triton featured here came to me as an unfinished project with a 1956 T6 Triumph Thunderbird 650cc engine in a McIntosh replica Featherbed frame. I owned a ‘56 Thunderbird for many years and before that it belonged to my father. Back in the late 1970s Dad and I both rode 750 Bonnevilles. They were great days on great bikes but we moved on and our Triumphs were eventually consigned to memories, until 1997 when Dad spotted the T-Bird and decided we must have it!

Being 21 years older, the Thunderbird was heavier, longer and lower than my old Bonnie. It steered slower and, naturally, had less power. I used to think “if only I could get this thing around a corner”.

My mind increasingly turned towards building a Triton, but conflicting emotions would take hold whenever I contemplated how much of the Thunderbird would end up consigned to the rubbish pile. Cognitive dissonance is a great motivator for doing nothing.

Aside from being road-going, national treasures, pre-unit Triumphs are aesthetically pleasing and trending towards the valuable. No one is urging owners to junk functional bikes to make hybrid specials. To the contrary, I would probably be kicked out of the classic motorcycle club should I even begin such a project.

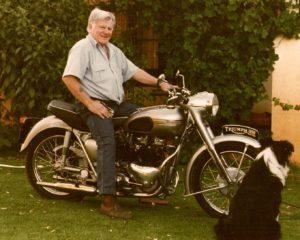

And, as if I need any more reasons, one of my favourite photos of my late father depicts him sitting on the Thunderbird with his trusty Border Collie alongside. No, if I wanted a Triton I would need to build one from parts or find a fully assembled machine.

I ended up settling for the latter, and she’s a gem.

The engine number in the Triton is so close to the one in the Thunderbird they could have been bedfellows. Replica frames are common-place but they vary in quality. McIntosh frames are made in New Zealand by Ken McIntosh and have a world-wide reputation as among the best.

They are arguably better than the real thing, as original Featherbed frames can be bent, broken and fatigued. A McIntosh bike currently holds the record for the fastest lap of the Isle of Man by a Manx Norton in the hands of Kiwi rider Bruce Anstey.

Triton aficionados and café racer tragics will recognise this bike has a host of refinements, including the highly desirable combination of Norton Roadholder forks, Akront alloy wheels and a Manx, twin-leading, drum brake. What’s not so recognisable is the five-speed gearbox, belt primary drive, 200-watt alternator conversion and electronic ignition hiding below the surface.

Evidently the bike had been sitting for some time. It was covered in a good layer of dust and had the obligatory puddle of oil under the engine. But, despite the neglected appearance, it was obvious the machine had the goods.

The engine was held together by all new fasteners and, brushing the dust away, the cases looked bright and new, clearly having been blasted by some form of media prior to reassembly. The lack of oil on the external engine surfaces, save for the sump at the very bottom, confirmed it probably had not been run for any length of time since assembly.

The engine was held together by all new fasteners and, brushing the dust away, the cases looked bright and new, clearly having been blasted by some form of media prior to reassembly. The lack of oil on the external engine surfaces, save for the sump at the very bottom, confirmed it probably had not been run for any length of time since assembly.

The presence of little rubber knobs still on the Dunlop TT100 tyres reinforced this. My Thunderbird spits copious quantities oil so it’s a relief to have an engine that is oil-tight.

The bike has been put together by a couple of legends of WA motorsports, one a mechanic, one a racer. Both are now in their eighties and still going strong. I hold onto visions of two old motorcycle wizards tinkering into the night working on their creation over cups of tea, which adds to the romance of a Manx-bred racing machine. I had great confidence in the quality of the build and, at the time of writing, there is nothing to suggest otherwise as the engine runs beautifully. In a final nod to the marriage between Norton and Triumph, I fitted Norton “Whistler” mufflers. The result is sublime.

So, what’s it like to ride? It’s too early to say as I still have a fair bit of tweaking but she’s licensed and on the road. One of the bike’s first test rides included a trip to the Dunsborough foreshore to celebrate the union of iron and alloy with the Silver Bullet Espresso, a 1962 Airstream Globetrotter.

Parts bin specials have never looked so bright.

EDITOR’ NOTE: Tritons are hard to find, but we’ve got one listed in ‘Bikes For Sale’. And yes, it’s in Perth. See it here.

What a beauty Dan! Well done mate, it’s one very tasty ‘Triton’

I’m ‘that friend’ who owned the Triton shown in the photo in Dan’s article, and yes, it has been one of my motorcycle selling regrets. It cost me $900 at the time (1977), it went like stink and was great fun — though you would have to fumble around every ten clicks or so reaching under the tank to turn the fuel tap back on as it would self close due to the vibration. Happy days!